I was just graduating from high school when Ben Shedd documented what Paul MacCready and his family had done. Having followed attempts at human-powered flight since was in 6 th grade, it a huge inspiration to me—changed the trajectory of my life. Now decades later, another gift from that era—walkalong gliding—allows me to give my students a real flying experience. It was another long shot, but I asked Ben whether he would be willing to talk about that extraordinary time. He was warm and accessible. He’s busy teaching university classes about film and pursuing various projects and I was not able to go out west to interview him myself, but I wrote down questions and his students Zach Voss and Glenn Landberg actually conducted the interview. Thanks guys.

When I have the time to do a really good job of editing the video with B-roll, I will. In the meantime, enjoy this draft transcript of his recollections of that historic, exciting time. My questions went beyond The Flight of the Gossamer Condor --fitting for someone who has led such an interesting life. Don't mind the numbers; just time code for when I edit the video.

(joking and laughing) Clapstick, take one.

Question about meeting Tyler MacCready

So we were working on the Gossamer Condor film and part of what was interesting was that it was—in many ways--a weekend family project. So Paul MacCready, who was designing and inventing it, brought his kids along. He had 3 sons: Parker, Tyler and Marshall and they were always there, part of the activity.

And so Tyler was the middle son. He had long blond hair at the time, I remember. And I remember Paul talking to me about the fact that he was working out and having his son work out on an exercise machine so he could get up his capacity to really cycle. Tyler and Parker, at the time, were both really experienced hang glider pilots and that was one of the reasons they knew how to fly the plane. They weren’t bicycle racers or anything like that, but that’s where they were in the piece.

So as we were filming the person who was the pilot in the beginning was Tyler MacCready and we became quite well acquainted just because we were working together closely. When we were making the film I always made sure that the pilot and Paul MacCready each had a radio mic on so we could get there conversations. So the primary conversations we got when we were first filming were always between Paul MacCready and his son talking back and forth.It was interesting that the project reached a point where Tyler wasn’t able to fly as long as he needed to or wanted to. The team decided that they needed a bicycle racer, somebody who had more power. One of the consultants who was helping Paul MacCready and the team brought in (a professional cyclist).

What was really interesting about the Gossamer Condor airplane was the maximum flying speed was 10 miles per hour. It was the slowest-flying plane in the world. It was usually flying about 7 or 8 miles per hour so the best times to film it were from 6 to 8 in the morning when there was no wind, or 6 to 8 in the evening when there was no wind. If there was a 3 to 5 mile per hour breeze that was like half the air speed, so it was down time. We all had a lot of time to stand around until the evening. 3:08 That was just the way it worked.

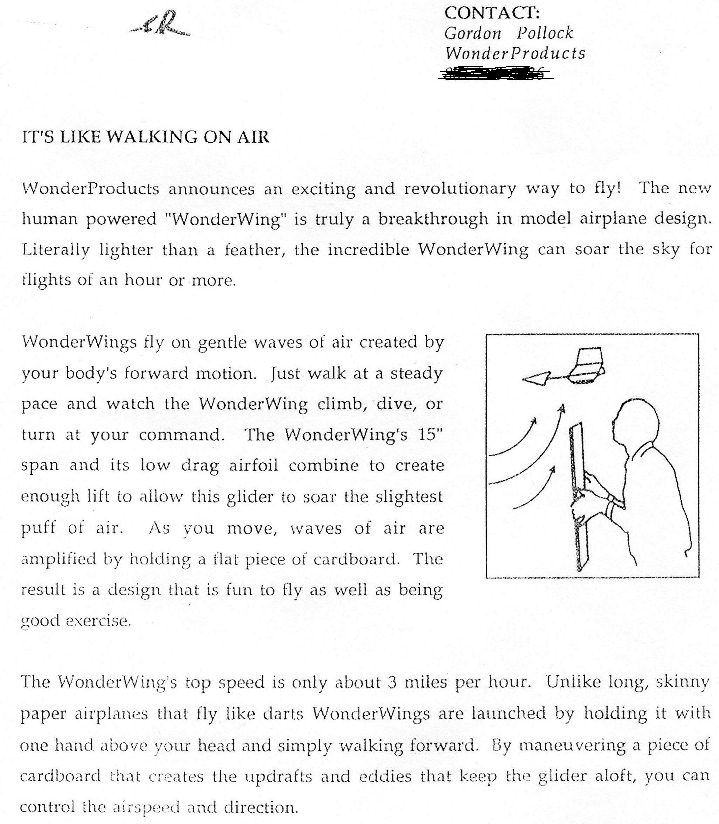

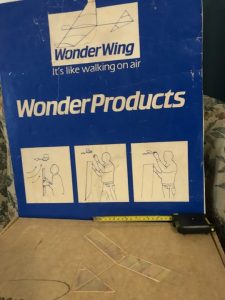

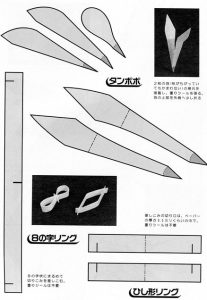

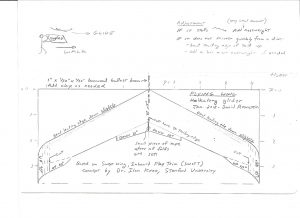

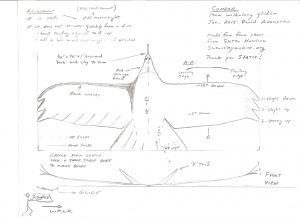

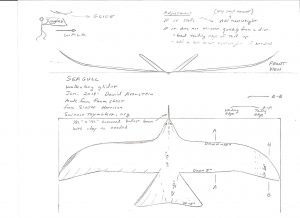

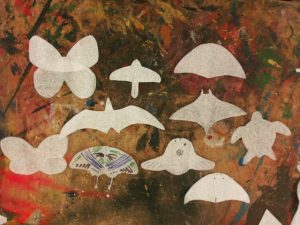

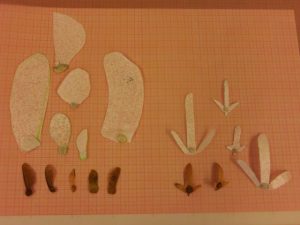

3:13 In the shop where they were building the Gossamer Condor there was all this stuff. There was a hanger and there was a huge table with chunks of Styrofoam, sticky tape, glue and people were just having fun building stuff. Somebody built a corrugated wing and it had a little dog house on it and Snoopy the dog from Charlie Brown sitting on it. And along the way Tyler MacCready built this shape—swept-back wings, tips at the end--which became the walkalong glider. And all of a sudden one day during the middle of the day I looked around and he was walking around with a piece of cardboard and he was pushing along (a glider in the air), making this air current. It’s something I knew nothing about. Air will go up the side of a mountain; he was basically making the whole mountain drift. Then if you flew it right you just walk along, you can guide it as smooth as could be. It was like, “Wow, look at that!” We had the camera there and we turned it on. In the movie there are two shots of Tyler MacCready, the only two shots we had, of him pushing that thing and making it go. There is was. 4:13 He was trying this thing out and I now see—looking back on it—that was like inventing the Gossamer Condor airplane. This was literally the first walkalong glider.

4:32 (Question about first seeing the walkalong glider)

(executive suggestion “tell me…)

5:20 When the walkalong glider happened everybody was thinking about things that were flying. We were trying to make the Gossamer Condor. One the who came in and was working on the project, Jack Lambie in a green shirt in the movie, he was one of the first people to put hang gliders together. He built them out of old plastic garbage bags and bamboo. That was the beginning of the structure of that sort of thing.

5:41 He kept coming in and out in a glider plane that popped up so he could take off by himself, he didn’t have to be towed into the air. The world of flight was what we were immersed in. My camera team was the observer, as it were, participating to a certain degree but mostly just watching them. Having this happen was just another events that wasn’t surprising at all. 6:03

As I think about it now it was a 14 year old kid walking around making this very finely shaped wing that would pick the air current up, stay level and fly at a very slow speed. Then about 10 years later I heard that Tyler had turned it into a toy that was being manufactured when he was in his mid twenties. I was not at all surprised about it. Very recently in 2007 when I saw Tyler, it was the 30 th anniversary of the human-powered airplane, there he was with his walkalong glider in his pocket.

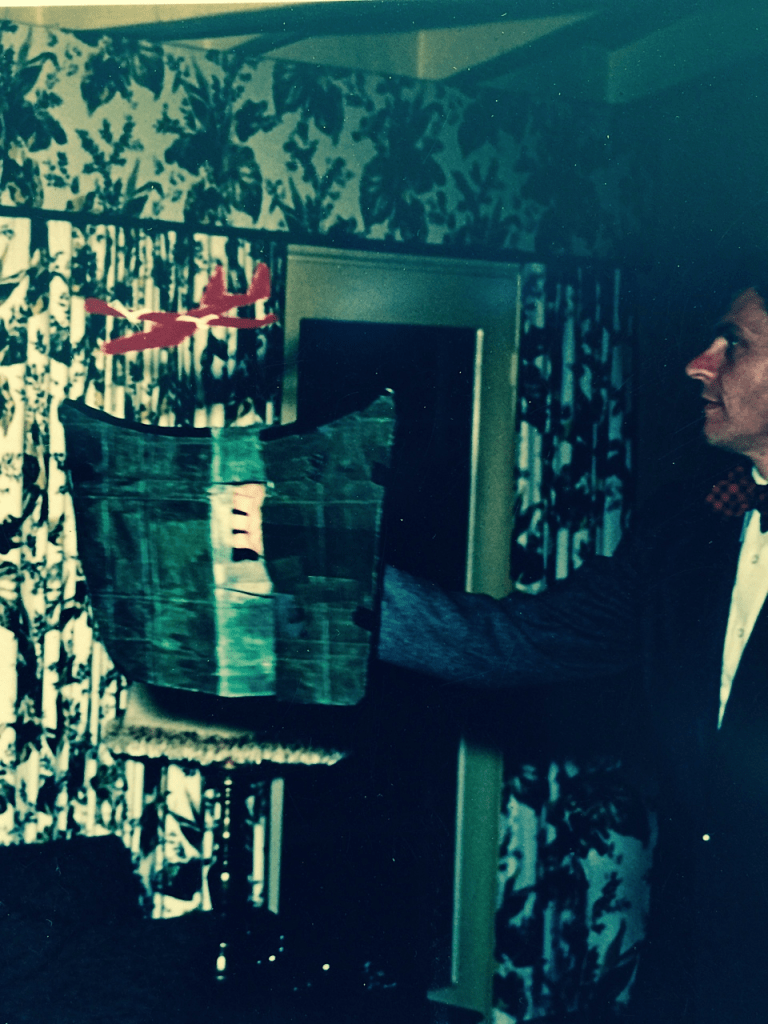

6:48 Let me tell you how the video came to be because that ties together as part of the story. When we first make the film it was shot in 16mm. This is 16mm film. The soundtrack was on it and this was the major way it was distributed when it first came out. That was the way it came out in 1979 until the mid 1980s. About that time video started showing up. This is the VHS box and here’s the VHS video. We made a beta master out of the 16mm. It turns out that this cover was one of the very first covers made on a page making program. It was 1985, just after PCS were out. This was the way it was distributed for the longest time.

7:41 Then about 2006 I got this interesting phone call from Brett Handley who was a curriculum writer at Project Lead the Way. Project Lead the Way is engineering for middle schools, high schools and career programming to get people prepared for college engineering programs. He said that as a school teacher he’d been using the Gossamer Condor film for years in his class and he loved it. He wanted to know if he could write it into the curriculum if it was available in DVD. 8:05 My first answer was, “Of course.”

I went and got that original 1985 tape and I tranfered it into my computer, I took the cover and I started making these DVDs to distribute. These were made one at a time off my computer. We sent a bunch of them to the Project Lead the Way folks and they tested them. They said it worked very well.

8:30 At about the same time the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was having a an ongoing screening of Academy Award winning documentary films. They contacted me and said, your year 1979 is going to come up in October of 2007. We’d like to get your original negative, now 30 years old, and make a brand new print of it. We’ll do that at our archive. 8:55 I said, fabulous. I gave it to them. They make a perfectly clean, brand new print. It looked beautiful. About the same time Paul MacCready’s company called me and asked if they could have 600 copies of DVDs so they could give it out on the 30 th anniversary to all their staff and employees at Aerovironment.

9:15 With the Project Lead the Way wanting a DVD, Aerovironment wanting a DVD and the Academy making this print we said let’s just take the print master and get it transferred as a DVD. So the Motion Picture Academy actually did the transfer for me off their brand new print. I paid for the cost of the transfer.9:33 Now we were able to make a DVD, the 30 th anniversary DVD.

At the same time I was working on another film that was all about doing an environmentally friendly, green building. We were making covers of this thin cardboard and so we did the same thing here for the Gossamer Condor. Even with the design of this thing I always liked it because you had to open it up all the way. The plane’s so big you can’t see it on the front, you have to see it all the way around. 10:00 It turned out that within a month we were able to get the DVD out and Project Lead the Way is using it in all their classrooms.

As part of that Tyer MacCready and Brian Allen, who was the final pilot, came to the screening the Academy had, as well as Jacquelyn Phillips Shedd—who’s the producer with me and my daughter who was 5 years old at the time the plane flew (now 30 years later so she’s an adult so she came to the screening); plus two members of the plane team, one of my crew members and my narrator Roger Steffens all came to this wonderful screening we had. At the end of the screening Tyler MacCready had one of the walkalongs in his pocket and he walked all over the stage using the ?????????? 10:49 and flying it right along.

Then along the way I bumped into Slater Harrison and this whole sciencetoymaker.org webpage and found that a lot of people were making these things. I made a couple of them out of the pages from a phone book 11:05 ??????? They’re very cool to fly around.

Question ???????

11:32 I was working on the Nova series on public television. The series at the time was 3 years old. I actually worked on program number one. I was associate producer. I was part of the very first team, second employee in the Nova series. Six Novas later I was looking for another project. Start over

Question about why had the confidence to invest so much into following the MacCready human-powered flight story

Let me start this over12:12 I was working on the Nova series in 1976 I was the second employee when the Nova series started in 1973 and worked on program one as an associate producer. I had done 6 Nova programs doing science documentaries on PBS. I’d come from California to live in Boston, working at WGBH for that period of time. I was back in California on a holiday. One of my film making friends, as I was having lunch, said, “My next door neighbor is going to win the Kremer Prize.” That’s how I first learned about all of this.

12:43 I said, “What’s that?” He said, it’s for a human-powered airplane. This guy Paul MacCready has the plans already and he really thinks he’s going to be able to do it. My brain went, wow this is cool! I could immediately imagine something rickety on a runway and it could take off and it would land and they’d have to do something more with it. Already I knew I had a beginning, middle and an end. From a filmmaking point of view this was like a fabulous thing to have. 13:08

I was like, Wow, so I said I want to meet him, can we do that? So they arranged for me to meet him, Paul MacCready. He had just come back from a vacation where he’ dreamed up this idea. His kids were hang gliding pilots and he’d written a technical article about hang gliding safety. He knew that the power need for a hang glider in theory was like one horsepower. He realized that if he made the wing of the hang glider 3 times as wide you get 9 times the area, you only need a third of a horsepower. Paul MacCready, in the back of his head he knew that humans could just produce about a third of a horsepower. That’s the maximum we can do even when we think we’re going fast. 13:45

Oh look at that. If I could do it I could make a human powered airplane. He said he remembered reading about this contest called the Kremer Prize. A man named Henry Kremer had put together a fifty thousand pound (British currency) prized with the Royal Aeronautical Society in England. It had been around for 15 or 17 years at the time. Coincidentally with that—and this is a very important part of the story—is that Dr. MacCready had cosigned on a loan for his brother-in-law for a catamaran company. That company, unfortunately, had gone belly up and he owed a hundred thousand dollars against that loan.

14:16 He was thinking, how can I get a hundred thousand dollars quick? Well that Kremer Prize is worth like fifty thousand pounds, I wonder how much a pound is worth to the dollar? He tells the story about looking it up as soon as he could in a newspaper and it was two dollars to the pound. So he said a hundred thousand dollars, well I should make the first human-powered airplane in history. 14:41

This person, Paul MacCready had made huge leaps. As I started doing research with him I learned that among other things he was the 1955 international soaring champion. He was the first American to win that. He’s said often that he can’t fly a soaring plane very well, but when he was a grduate student at Cal Tech doing his PhD. in the late 1940s he’s written a formula that compared forward speed to sinking speed on a glider. Then he interpolated that into a ring that goes around the variometer. He could just make an adjustment and it would give him the optimal speed in between thermals to stay aloft. Then he won the championship in 1955 by the widest margin anybody had ever won it. It’s nicknamed the “MacCready Ring.” So I already knew this person made these giant leaps.

This wasn’t something he was casually going to do. Plus he had a really interesting crew team. The guy who designed the airfoil, Peter Lissaman, worked for his company Aerovironment and he was one of the world’s greatest airfoil designers. He later did the Americas Cups boats and stuff like that. Having him design the wing was going to be just right.

1600 Jack Lambie was one of the inventors of hang gliders. One of the other people

sorry I cannot remember his name ??????? worked in the jet propulsion laboratory and he was head of satellite programs. They all agreed to do this on weekends.

1615 MacCready showed me a bunch of his plans. I didn’t have justification to just say I’m going to do this project. I took the idea and I went back. I had to learn about flight; I didn’t know anything about airplane flight, I’m not a pilot. So I did my normal Nova research into a new topic. I steeped myself in how planes flew. I went back to the first gliders in the 1870s, 1880s Otto Lilienthal. I started learning what they were trying to do, and the similarities and differences to what MacCready wanted to do. Then I had an opportunity to do a research project where I was trying to figure out what the next NOVA program was. At the time I was going to do methadone maintenance and/or addiction to coffee or car safety--I watched lots of crash films. Or human-powered flight. Because I had 3 of them it took me on a research circuit so I could spend a day with Paul MacCready.

He showed me his sketches that he had drawn of all of these things and explained what the idea was. He told me exactly how motivated he was: because he needed the money. As he’s said over the years, that’s a really good thing! High motivation, you don’t stop casually. The other part of it was one of the plans he showed me—and he explained it—was called wing loading: the area of the wing vs. the weight 1721

All the human-powered airplanes that had been built up until the Gossamer Condor had a wing loading of about 1 pound per square foot. The issue is you have to build a huge wing because you have such a small amount of power. Airplanes had always been built with all this internal structure inside the wings. So that was the puzzle. To make a big wing it gets heavier and heavier. MacCready’s idea was to use a hang glider design, which was basically a tall strut this way 1753 (vertical) and a cross bar and then these triangulated wires. If you think about triangles if it was sitting on the ground this triangle would hold the wing. Then there was a ?????? blue triangle beneath the wing, so there was like no weight. All of a sudden the plans said point 2 (.2) pounds per square foot.

I saw this huge leap. Nothing before had .2 lbs per sqauare foot. I said this is a really cool film to be made here and I should follow him as long as I can. If it eventually fails, well, it’s going to be the best attempt ever. I was able to raise money on that. 1825

I’m a documentary film maker and I write the whole script in advance and I wrote a whole script. It actually starts with the plane winning the Kremer prize then went back in time. I wrote the whole script as if it had already happened. Based on my research it had a crash in the middle. When you actually watch the film it has 3 crashes in the middle! There were more crashes than I had in the script but they were inventing something brand new.1856

So I knew it was something really worthwhile to do. I went back to public television and got a contract to go. I left NOVA to start this movie by myself and start my brand new company, Shedd Productions. Off we went.

1910 We had a guarantee in the contract that at a point in February, it would last 6 months after we started. Past that point we would have to finish the film. I called my mentor who was the guy I’d worked with at NOVA the very first year Simon Campbell-Jones. He was a BBC senior producer. He came to the ‘States to teach us Americans in how to do these kinds of programs which was very helpful. He went back to the BBC and he was running the science series over there, Horizon, which was like NOVA.

1942 I called him up and asked if he’d made any movies about human-powered airplanes, there’s this English prize? He said yeah, we have a bunch of them on the shelf but none of them ever work so we just keep waiting. So I said ok. I didn’t tell him at the time what I was doing because I wanted to make sure I could do a much with MacCready as I could.

1953 S we went to work making a movie. I hired Boyd Estus Boyd was a senior camera person at public television where NOVA was coming from, WGBH. This was his first independent project and with the guarantee he bought a brand new camera and came out to California to start shooting. We had done 4 NOVAs together so we really knew how to work with each other.

2014 Then we hired a local out of California. We were based in Los Angelis. The airplane, the Gossamer Condor, was originally flying at the Mohave Airport. It was an hour and a half drive to get out there. On some mornings MacCready would call us and say, we’re flying today. I’d call Boyd and say we’re flying today. I’d drive there and we’d have all the camera equipment and off we’d go. We’d get there just about the time they were starting. We’d film, then they’d sit around when the wind was blowing 3 or 4 miles per hour, until evening time. Then it cooled down and we could fly a little more. That was our routine that went on and on. They decided that the wind was too high at Mohave and so they moved it all to the Shafter Airport.

Question 2140

When I started this project I had a lot of experience by then doing documentaries. I’d done 6 NOVAs, pieces and educational films before that on .…… start over

When 2208 I jumped into the Gossamer Condor film, up until that point I’d worked for other companies making movies. I worked for public television, I worked for Churchill Films Educational House. I’d been a graduate student making films in graduate school. When this project came along I recognized that we were going to have to cinéma vérité : film it as it happened. We were going to always be alert and ready to go, something I’d already learned how to do in some ways. In my professional background I’d started as an editor. I was thinking about what the editing pieces are you need to put it together, which helps me a lot when I’m trying to direct something. We’ve got the wide shots, get the close ups and the different angles.

Boyd Estus 2248 and I had done a couple of very vérité sequences in the NOVA series and we’d them up and we’d set them up and film things as they happened along the way. So we both knew how to do this independently and together. 2257

When MacCready and his team started they figured it was a 4 month project. They were going to use the square-shaped wing. When you look at that picture of the airplane it’s got a very much slanted back wing but this is the second generation that they had to build. They had to learn along the way. 2318 We had to make sure we were filming the bits and pieces going on.

My original plan was that this was going to be an hour-long PBS show. Then we were there filming and filming. As we did a count and they did a count at the end there were over 400 test flights. We filmed almost all of them because we couldn’t miss it as it happened. While we were shooting any given day they were doing something. We’re working with Boyd, always getting different angles so we could have one angle with the plane taking off and another angle with the plane flying and we could—later—cut it together even though they were different flights. That was our habit. We knew we were going to be rolling through film. That was part of the goal, that was in the budget. We budgeted for 4 months of crew time. I think we budgeted for 20 or 25 days of shooting. I knew that was part of the thing I had to take on. 2411

As it became apparent to both MacCready and to me that it was going to take longer we had to keep finding ways to put it together. There’s one credit section at the end of the film where it’s additional photography and there’s a whole bunch of photographers 2424 We used some stock footage that we got. I shot some of the footage. Boyd shot as much of the footage as he could until we absolutely ran out of money and then we had to keep filming anyway. My company was a complete startup. This was doing business as Shedd Productions. As we started going along we actually passed the cutoff date. We had it in the contract that it couldn’t be cancelled. Then Jacquelyn—Jacquelyn Phillips Shedd who was the producer with me—was doing a lot of the phone negotiating with WGBH and PBS, trying to make this work together. We figured out that from the PBS side this invention wasn’t going to happen in time for the air-date. So they wrote the project off at public television, not surprising from their side. I’m looking back at this from many years now, 3 decades plus, but at the time it was very stressing. 2520

Then we actually negotiated a deal with my colleague Simon Campbell-Jones of the BBC because I talked to him about the project. If he would license stock footage rights, he could make the whole show. Then he could license it to public television and public television would make sure all the rights went to Shedd Productions. That’s the triangle that happened. So in the course of giving you this answer …

Jump 2600 Making the movie was going along fine. We were editing, it was coming together. There’s a sequence in the film where Greg Miller, who was the second pilot, made this very long flight. It was like a 4 minute flight and it happened in the afternoon. That actually occurred in part because I needed to show the funders that the plane could do long flights. For the purpose of the research they could do short flights and they could tell what was going on just fine. On that particular flight while they were getting ready it was dusk. I was helping with the dolly and pulling the plane back while we were getting ready. I walked all the way to the other end of the runway while the conversation was going on. I quietly said to Gregg Miller, “I’ll give you 50 bucks to fly it to the other end of the runway.” I knew he was a bicycle racer and he needed a prize and all of a sudden there was the world’s longest flight happened as a result of that! It excited every there and it also gave me a piece of footage to show everybody that the plane was really very significant. 2700

Unfortunately the air-date still wasn’t going to happen and we did negotiate that out and figure it out. In the long run we went from just making a movie to suddenly being very business savvy about what we needed to do to get the movie finished. All the rights were given over to Shedd Productions. I license a whole bunch of material to the BBC which game me enough money to continue making the movie, to finish it. Then it was licensed to public. It was shown as a 2724 ?????? children on the NOVA series. In the mean time I went back to Churchill films where I’d worked out Educational Film House and said I have all this footage and I’d like to make a half-hour film out of it for the educational film market. They got very enthusiastic, gave me an editing room and a slight advance which gave me a different way to get the film finished. That’s the Flight of the Gossamer Condor the 27 minute movie that’s the finished movie. From my side there’s also this hour version that was on PBS that cycled around for a little while.2756

Following that I’ve gone on and made many other films. Jacquelyn went on to law school and become a lawyer because she was so good at doing the negotiating. We all sort of found our niches. This was the first independent project I’d ever done. The thing that I knew while I was making the film was how motivated MacCready was, how creative he was and what kinds of leaps he’d done before. There were orders of magnitude leaps. So I had a hundred percent confidence that it would happen. MacCready would say on any given day, we have ninety-nine percent chance of it happening. And I learned that one percent is big enough to drive a Mack truck through! 2838

I also learned in the process was, because this was a flight that had to win the Kremer Prize, it was a very official course. It was two pylons a half-mile apart; the plane had to be 10 feet high at the start and end, there had to be observers who were outside the team. So the first couple of times they tried the flight I realized very quickly the plane probably wasn’t going to complete the flight then. The point was to get the course in place and get the observers coming out. That happened over and over and made sense. 2905

It was clear to me from a couple of conversations with MacCready and the like that they weren’t going to stop. They had that motivation. It took them almost a year and we were able to find the funds to put it all together.

One of the things I had to do when I was putting the movie together and finishing it—there’s a title card at the beginning that says this actually happened. In some ways this is old history, it’s getting further and further back in time so part of the puzzle is how to keep it current. When we were making the film we were writing the narration. I remember exactly when it happened: I was under the weather and one of my old San Francisco State filmmaking roommates buddies of mine. We were working on the narration. It was all written in the past tense. This happened, that happened. We went through and took every “was” and turned it into an “is”. We took out everything that was in the past. Documentaries often tell you something that happened in the past. 3008

There’s a point in the movie where the propeller is put on the airplane. First you see it being pushed then it starts flying on its own. The narration is a grammatically incorrect sentence. It said, “And the then the Gossamer Condor is born!” and after that all the narration is written in the present tense. So we’re all traveling along together, not really sure how it’s going to happen. The narration was all written very carefully so it doesn’t tell you what’s going to happen. 3032

Something I learned on NOVA, to write what’s in the picture and be observing about it. So the narrator has maybe just a little bit of knowledge, slightly different than I do a a viewer, but we’re kind of sitting together listening to it and watching it happen. So that part of it makes the story very present again. Pretty soon your completely lost…you’re not quite sure when it’s going to happen, if it’s going to happen. The plane has a couple of fairly major crashes, so just when you think it’s really working well it breaks again. 3058

It turns out that every time it breaks ….

One of the things that’s really useful about the airplane and about MacCready’s style that I learned quite early on is that if something broke that meant it was just beyond the threshold of flyability—that’s what I called it. They had to tune it back a little bit. So if the tube would bend and break they’d just make a sleeve to fit over it and back it off, back it off. Then in early August of ’77 when it really crashed because a control wire slipped off a pulley they had to rebuild the whole plane. In the course of rebuilding the plane they took off 7 pounds. It was 70 pound plane at the end; they basically took ten percent of the weight off.3137just by taking off all the extra tape off and all these repair pieces. That gave it better wing loading and made it more flyable. 3145

In the mean time Bryan Allen, who was the third pilot, he was a hang glider pilot and a bicycle racer. He was bicycling 30 or 40 miles a day. He got this job was because he was Sam Duran--who was one of the guys building the plane--he was his roommate and he was out of work. He just happened to be standing around. There he was, the right size, the right weight, the right skills, the right ability to fly and he became the pilot. And all of a sudden the plane got better and better as well. The second pilot, Greg Miller, was a bicycle racer and he had to get back to his bicycle racing. 3222

One of the really interesting series of things that happened when different people showed up and added some new skills that they took advantage of and make it work together.

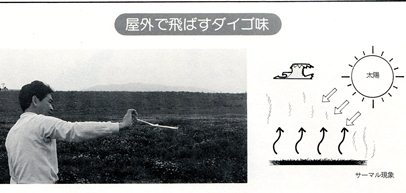

3246What was really cool about Tyler MacCready, he had his piece of cardboard and he was pushing the wind over the top of it and making the walkalong fly. What’s interesting about that whole project is the one thing that makes it work is the mass of air, something you can’t see. What I had to learn along the way is that we swim in ocean of air. It’s much less dense than the ocean of water, but this is thick, heavy stuff here. I had to learn about that. 3315

There’s a sequence in the Gossamer Condor film where the plane is flying along. It’s the first big attempt and it starts tipping to one side. It tips and it tips and eventually it crumples into the ground because they can’t get it to tip back. What I learned about that is that there’s this process, this phenomenon called “apparent mass.” So a plane wing flies and the mass of the wing is very key but it’s also the mass of the air around it—this bubble of air, as it were—that’s part of the mass of the whole movement. Jets and propeller planes, they fly so fast that they basically push through it and don’t create so much of a problem with apparent mass. 2356 The issue with the Gossamer Condor is it was flying so slow that the weight of the air, the mass of the air is so heavy that once it starts going you can’t easily push it back.

Eventually to make it turn they end up putting lift on the inside wing which starts dragging it backwards and doesn’t let the wing drop. It drags it backwards and that’s what turns it, which is exactly how the Wright brothers did their turning as well. MacCready called me one day and said we did this test on the wing. We took the balsa wood model and we put it under water and I could feel it was the wrong shape. I‘m going to redo that. I clearly didn’t have a crew there to shoot that but I also realized that it would be very cool to shoot that and be able to take the camera under water because the mass that’s analogous to the mass of the air, you could see it. So that one sequence was the one we recreated later. Paul MacCready and Tyler are outside in their swimming pool. It was actually in late fall or early winter and it was freezing cold. We went and rented a waterproof camera housing. That camera man was Fred Elmes who shot a number of features and he was working on independent films like this and I hired him for the day. He had a wet suit on so he could stay warm. We knew we had to do this angle of MacCready putting it under water. Then we did this one were we actually submerge under the water with it so you can see the mass. I had tried to give this invisible thing visibility.

I have now watched the film hundreds of times. 3534 I’ve discovered that if I watch the sequence where the plane is making this attempt and it starts gradually tipping to the side and imagining that there’s a mass of air you can virtually see the mass of air in your brain. And it’s the same mass of air that Tyler MacCready was creating, or pushing with this piece of cardboard, making that shift. I remember bicycling one day where there was a slight breeze blowing on me and I suddenly could really feel the mass of air. Bicycling is one of those ways you can feel it slipping by you. The whole movie is predicated on the fact that the plane is flying in the ocean of air, which you can’t see. Our eyes don’t pick it up, cameras don’t pick it up. So I had to find every was I could to indicate it. 3620

In the movie itself at the very beginning they had a bunch of streamers on the plane. You can see them moving in the wind. Every time there was some kind of effect like that those were the sequences that I as and editor pulled in so we could begin to imagine the air. 3635

There’s one still shot… When we were shooting we didn’t have any tome to shoot any stills of the plane. We also knew that we had to stay away from the wires. We didn’t want to interfere with their research project. 3651 But also I wanted to get a shot of Boyd Estus shooting a piece. There’s one still where Bryan Allen is flying right by the camera crew. If you look at the still there’re two shadows on the ground. One of them is me taking the still. And it turns out that is also a shop we used in the movie because it was this great shot where the plane came very close and flew right by us. That didn’t happen very often we were normally because we wanted to make sure we were away from the wires, which were piano wires we could get tangled in. but we made that shot work…very carefully. 3724

Another thing that was very interesting was … the Kremer Prize was to fly the plane a mile. That’s a long distance. As the plane kept getting better and better we had to keep finding ways to track along and follow the plane. At the beginning we had what we call a “doorway dolly.” The camera was sitting on a milk crate there was like a flat wagon. I was pulling it along and running as fast as I could as Boyd was shooting. 3745

Then pretty soon the plane started going longer distances so we went to a rent-a-wreck place that was near Shafter Airport and we rented this convertible car for like ten dollars a day. It was a Dodge Dart. We took the back seat out of it and put the tripod in so we could drive along. Sometimes we would borrow somebody’s station wagon so we could sit and stand on the back bumper and drive along. That became part of the challenge was to stay close enough to the plane so you could see it while it was covering huge long distances. It was one of these growing processes that I as a filmmaker had to figure out on the go. We had enough budget for it more or less.3825

At one point when the plane actually crinkles and bends the first time you see it in the movie and they say, let’s drag it back to the hanger. They use our camera dolly as the dolly to tow it back because they’d never expected to do that. Then they eventually built their own dolly so they could move the plane around.

Question 3900 about progression of technology

I’ve been making movies since I was a kid. My dad, I started acting in his movies…3917 I’ve been making movies literally since I was a kid. My dad who was a sign painter wanted to tell stories and teach us history. He actually made my brother and me knight’s outfits, Prince Valiant outfits. All the kids in the neighborhood wanted them. The next door neighbor owned a camera shop and he brought home an 8mm camera. We made our first movie which was Knights of the Square Table and I was Prince Valiant. 3939

Over the years then I moved into 16mm when I was working as a professional. Then video shows up along the way. And as video was growing I made a shift and I worked in IMAX. IMAX is 70mm film, it’s this size film, it’s big. You edit this in 35mm, you have it printed down. I was doing that and now we’ve moved into the digital age. There are actually some cameras that can shoot this much data. It’s a lot of data. It’s like 4000 by 4000 pixels. It’s a huge amount of information and it’s just now coming of age probably 25 years after this came out. Now we can actually do this in digital as well. Those changes are all interesting. 4020

The other thing I did as a kid is I was a magician. My oldest memory is 2 years old and seeing my uncle doing a magic show in my back yard. Then I learned to do some magic tricks when I was 5 or 6 and I was a working magician.

So I’m always creating these illusions of reality and that’s about juxtaposing things together. So the audience goes on a time line and thinks they’re on this interesting adventure.

The technology keeps changing along the way and we now have capacities on our computers to do the editing. We have cameras that are very cost effective to capture lots of high-resolution data. On one hand it’s like everybody can make a movie; on the other hand you have to have the experience to know what to do with the material and how to put it together. 4058

I find that sometimes it’s easier now to work with smaller teams. But the big puzzle, it’s still a puzzle, you have an audience for amount of linear time. You have to have a beginning and an end. You have to have juxtapositions and make sure there’s an interesting summary at the end. Then it’s always important to give everybody credit at the end because a lot of people have to come together. It’s not done usually by one person.

Question 4141

I have two college degrees in filmmaking: An undergraduate at San Francisco State which is very much a documentary, art film-making school; then a graduate degree from USC’s School of Cinematic Arts which is much more about theatrical filmmaking. After I graduated from USC my intention was—my degree was in making movies—and I made movies all the way through the Gossamer Condor film. When that film was over I was trying to figure out what to do next.

Pickup 4220 As I was finishing the Gossamer Condor film one of my good friends in Los Angeles, Mitchell Block and I wanted to do a class in how to produce films. We submitted it to USC where I graduated and they said, well, we can’t do that right now but a professor I’d taken my beginning filmmaking class from, Mel Sloan, invited me to co-teach the class with him. So my very first time teaching was in the same classroom that I’d taken a class about making films, and with the same professor. It turned out to be very interesting. I really enjoyed doing the teaching. My background was not in teaching but in the same way not in science but I learned very quickly about the processes I needed to do. During that semester—this was January 1979—that was the semester the Gossamer Condor film got the Oscar . That of course was wonderful at school. I asked if we could teach that other class on producing with Mitch Block and we started that summer. We did that for 30 semesters at USC, 10 years 1979 to ’89. We also started teaching at Cal Arts 1985 to ’89 and at Cal Arts there these students like John Lasseter and the folks at Pixar. 4344

Question

My background in filmmaking…

In the process of making films I’ve always had to work with groups and having a classroom of people is also a group. In many ways I’ve set up a class that’s very much like a professional production. We’re able to let it be a professional seminar. There’s a bunch of structure to it. This class about producing has worked very well. It was wonderful when I was teaching at USC film school, some of the students are about 20 years into their careers. Dan Roach ?????Do you mean Jay Roach has done all the ?????????? and the Austin Powers movies was in one of my classes. Bud Shcaetzle has done piles and piles of music videos, everybody from Tina Turner to Garth Brooks was in the class. Bob Weide was in the class. He did Curb Your Enthusiasm. 4431 They were all students.

Then in 1989 I got offered a really interesting year to be an endowed fellow, professor at University of New Mexico. They had an arts professorship that moved around. So I ended up teaching 6 film classes for a year. I moved to Albuquerque from Los Angeles. At the same time I was making IMAX movies so I was able to do both. 4507

My wife got an invitation to a mid-career fellowship at Princeton University. I went back to Princeton and was making some IMAX movies when I bumped into 18 foot by 16 foot by 6 foot ??????? computer screen they were doing with a lot of little screens put together. It was a research project at the time. We’re seeing more of those these days but at the time I said wow, an IMAX film sized screen. We could teach a design class in there. I ended up teaching at Princeton as a Senior Research Scholar for 6 years with a design screen. 4537

Then we came to Boise Idaho where Janine is the director of the Discovery Center here, the science museum here. It was really wonderful to be able to slip onto the faculty here and teach at Boise State. 4607

Question about why Boise State

I’m currently based in Boise Idaho. This is the Sixth city I’ve lived in. I grew up in California, lived in San Francisco and Los Angeles. I went to Boston when I was working for WGBH. Came back to Los Angeles for 17 years. I moved to Albuquerque New Mexico for 8 years then Princeton for 6 years and now I’m living in Boise Idaho. I keep finding these really interesting places to live that usually have skiing, which I love to do, and lots of outdoor activities. They are interesting university places where I can find libraries and I love being in the environment where people are thinking of new ideas. 4642

When I was working on the NOVA series the thing we did all the time was go to universities where scientists and professors were working. I went to Princeton University originally on the NOVA series years before I ever went there as a faculty member interviewing some of the professors there. When I was working at the NOVA series we determined right at the beginning that the series had to go all over the United States because it was a national series. In the course of the three years I was working at NOVA I traveled to 46 states because that’s were people were doing their work. 4723

Then when I started doing IMAX films with the huge screens, those are also pieces that take audiences all around the world. One of the films I did was on tropical rainforests. It ended up that we got to do this in a very interesting trip around the equator. We shot in Costa Rica, Malaysia, and Australia. 4750

There’s a wonderful university where I’m based now in Boise Idaho, fabulous ski area and a very good, active film community. One of the projects we’ve done here … 4823

I’ve taught basic production, advance production here and am now teaching the production class. I’ve been finding a rather interesting community of professionals and a number of students have lots of experience. A couple of years ago the Make-A-Wish Foundation approached my daughter’s school to work with a12 year old kid named Mitch Kohler who had degenerative spinal atrophy and he wanted to be Luke in Star Wars. I came in and started helping and pretty soon it got to be a fairly big project. A friend of mine named Doug 4849 Cole worked with 6 th graders and wrote the script. We did this project called Star Waiters, which you can find on YouTube under Mitch’s Make a Wish or Star Waiters. It’s a 35 minute Star Wars fan film. 4903

On the production we shot for 3 days and edited for 3 weeks with a number of professional folks who all volunteered their time—it was an all-volunteer project. Lucas Films donated all the music and actually sent the sound editor and the real sound effects from Star Wars to edit into the sound track. 4820

Star Waiters got the Best Comedy Short at the Idaho Film Festival. It made me laugh a lot because here’s a very slick project with 12 year old kids, much like I was a 12 year old kid making movies.

For me it was no surprise that later the Make a Wish Foundation of America chose it in 2009 out of 13,200 wishes as the Wish of the Year which best showed how a community comes together to grant a child’s wish. It made me realize that every time I make a movie you bring a bunch of specialists together and bring a community together to make a movie. It’s just what you do and it was lovely to have that language and to hear about it from the national foundation.

Question about deliver a message to youth 50:33

As I’ve moved through my professional career making films and teaching career I’ve discovered it’s interesting to look in 5 year chunks. At any point in time I’ve just finished a 5-year period of work, I’m just starting another 5-year period, and I’m in the middle of a 5-year period as well. I kind of see those as different kinds of changes and transitions that happen. The more I understand subjects as I make my movies, the more I understand the bottom-line content. That’s why I can do science films well. Learn what the reality is then figure out how to tell stories. 5116

I set some very specific criteria for myself about what my stories want to be like. They’re gender-neutral, multi-cultural, intergenerational—grandparents and grandchildren should be able to watch them together. Nobody should get fidgety. I find that as I set those criteria for myself as a maker of movies, I’m also a viewer of movies—as we all are—and I hear stories. I think stories are really wonderful in our culture. They become the way we understand things. It’s lovely that the Gossamer Condor story, which is now 34years old, has this longevity. People are constantly able to come to it fresh. 51:57

I see that there are a number of stories in our culture that we have for hundreds of years and thousands of years. One of the IMAX films I worked on, Tropical Rainforests, is all about evolution. I had to think millions and tens of millions and hundreds of millions of years and how to get these numbers in mind. I came across this quote that John McPhee, the Pulitzer Prize winning writer put in one of his books Basin and Range5221 in which he put this little section in that said five-thousand years, fifty-thousand years will have a nearly equal effect on all the imagination, to the point paralysis. As a filmmaker I’d like to awe people’s imaginations but I don’t want to awe them to the point of paralysis. When I was making my IMAX movie on hundreds of millions of years, I found how to get people to think about that. I started the narration using one of John MacPhee’s words, which was imagine we’re travelers in time, it’s four hundred million years ago. 5252

I’ve been able to teach myself to think like that and then be able to use movies to collapse time. That’s what’s so cool about the Gossamer Condor film. In 27 minutes it does a year. The tropical rainforest film in 33 minutes does 400,000,000 years. Once I got used to collapsing time where you just jump along and view things it all make sense. I keep finding the really valuable stories have long time longevity. They give me ways of thinking about my future and about my past. 5325

I keep trying to make those kinds of stories. They’re the ones where you look around and put some filters on and say, what’s that story that will have some longevity to it? It won’t have a 10 year shelf life. That’s not only from having a vision of what the story can do over time; it’s also very practical. It means people will keep watching it and watching it, so you get more money to make movies in the future. 5357

I think about what stories come along. Looking at my life and career I started making movies when I was 7 and it’s all I’ve ever done. When I was a kid they were my dad’s movies. And much like Tyler MacCready who was making this walkalong glider when he was a kid, he was just doing what his dad did, which was go and invent airplanes. As adults we have both kind of ended up just naturally doing what we’ve always done along the course of our lives. 5428

When one is a kid one tends to things that parents or family or grandparents or people around you are doing, and you end up with this collection of abilities. I know how to make movies naturally. I cut one of the movies my dad made when I was 12 years old. I didn’t necessarily know right from wrong, but I learned right away what was working and wasn’t working. Some of it was trial and error but it’s just naturally what we do. 5457 It’s interesting to—not necessarily pay attention to what we’re doing when we’re kids, but to not forget that we’re actually building pieces of experience that we draw on all through out life.

Question 5526

IMAX theatres until about 5 years ago were mostly in science museums. I’ve spent a lot of time in science museums. My wife is the director of a science museum. The Discovery Center here in Boise, Idaho held an alternative energy festival in 2005 or 6. I went and I heard this guy—

Gary Christensen--talking about this building he was going to build. It was going to be efficient at all levels. I went and introduced myself because it sounded like a great story. They were literally pouring the cement for the building, the Banner Bank building in Boise. His goal was to build a LEED ® Platinum building. The U.S. Green Building Council has come up with their criteria, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design. 5619

We started really following it. I was taking still pictures. It was kind of the opposite of the Gossamer Condor. We didn’t have any money at the beginning so I was doing stills, which we ended up animating. 5633

When I heard Gary Christensen’s goals for his building it was obvious that this was also someone who was taking a big leap because of his ambitions and how he was supporting his group. We ended up making this documentar--and this is Gary’s title--Green is the Color of Money. This was the 18 th LEED ® Platinium Building in the world at the time. It was the first LEAD Platinum building ever built by a private developer with a goal to make money. He wasn’t a green guy at the beginning trying to show off environmental stuff. He was a banker and appraiser. He realized that when he brought his energy costs way down, the value of his building went way up. It was a wonderful story. Plus, it was a whole bunch of local people, local colleges, local training who were given the goal to make this thing work.

There’s a wonderful book called Natural Capitalism that Paul Hawken and Amory and Hunter Lovins wrote that Gary Christensen read at the very beginning that outlined how to make this happen. I coincidentally had read that book about 5 years ago and I brought my copy in and showed Gary. He had given copies of Natural Capitalism to his entire design team and said, build me that building. They did it and it’s an example of how you can make a highly energy efficient building using normal materials, normal cost. That’s what’s really cool about this story. 5758

When I was finishing this piece I wanted to write some kind of a one liner. I asked the architects, can I say that this is one of the most energy efficient buildings in the world? They said that it’s easy to say it’s one of the 50 most energy efficient buildings in the entire world, probably in the top 5 or 10 actually, even now. Wow, how cool is that! 5821

In any movie you watch, some kind of change happens from the beginning to the end. In the course of the 30 minutes here the whole issue about should I do this and could I do it cost effectively all goes away. You discover you can make much more money with it, and do it with a bunch of smart, local people and bring it together. 5907

Question family credits

When we were working on the Gossamer Condor film, we went way past the cutoff date on the contract and went way past our money. More and more we had to call in friends and family. I called in my brother who was a river guide and very good with his hands. He came and worked on the airplane for awhile in between his other projects. Then pretty soon I needed to borrow some family money. I got support form my parents and in-laws. At the time my older daughter was 5 years old. She was always there in the editing room and always working around—so they all got credits at the end of the movie. Yes indeed it was a family production. 5948

When I first started the company I had to get going right away. One of the things you can do is use your name, so it was Shedd Productions. It wasn’t like we spent any time thinking about it. We had to write a contract and move.

Questions about being a magician.

My oldest memory as a child is watching my great uncle doing a magic show. He was from a magic convention and he came through our neighborhood in California. He stopped and did a show. I was two or two and a half and if I stop and think about it there are still two or three tricks I can see him doing: turning water into wine, making a card come up…and so by the time I was 5 one of my cousins taught me how to do a magic trick. The trick was here’s the coin and you go like that [Ben does the trick, it’s impressive]And it’s gone here. And it comes back here. This has been with me since I was tiny. 10039

As an adult I’ve had a very long career making documentaries. The documentaries that people really want to pay attention to, I’ve realized, use magic techniques. I’m creating an illusion of reality. Documentaries are not reality. Their time is compressed and all these kinds of things have to happen, and they are in many ways wonderful illusions. They make you suspend your disbelief and you watch them. I’ve looked back and said, oh look they’re magic tricks.

intro

I’m Ben Shedd. I’m a director, producer, writer and editor. I make movies, I make videos. I now make digital—I call it moving image media. I’ve worked in everything from 8mm to IMAX.