So you’ve seen a video of air-surfing, AKA walkalong gliding. It looks really cool and you’re thinking how much you’d like to do it with your school students/ scouts/ camp/ learning festival or homeschool group. But you want to know what you’re getting into. You want some details, like what age groups will it work with, how to start, how much time and space are needed, how to prepare, etc. You’ve come to the right place. For the past 8 years I’ve been happily obsessed with walkalong gliders. I’ve taught lots of people how to fly in schools, science museums and events; learn from my experience (translation: learn from my mistakes)!

Consider trying simple paper walkalong gliders first (“free and frustrating”).

Paper gliders are easy to make and a complete pain in the neck to adjust, launch and fly–but worth the effort!

From my own experience and from years of getting feedback from people, I noticed something: groups who struggle with paper gliders first tend to do exceptionally well when they switch to foam gliders. And I do mean “struggle”! Paper gliders are much heavier and difficult to launch. The bend angle has to be just so. Expect moaning and gnashing of teeth. But they seem to gain something by trying (hmmm, sounds like a metaphor for life). Furthermore, newbies wreck gliders with their nervous fingers and general carelessness. But with paper gliders it doesn’t matter! They are quick, easy to make and cost essentially nothing. If YouTube is blocked at your school, you can still view this compressed video instructions. The video starts with lauching the gliders up in helicopters, but there are also instructions for flying them as walkalong gliders. Here is the transcript of the narration, plus some additional details.

Emphasize to the group that the foam/gliders are very delicate.

All other challenges can be corrected, but if a kid mangles their foam glider, it is difficult to repair (see start with paper, just above). The Achilles heel of light foam gliders is their fragility. Kids, and even adults, do not naturally show the amount of care that is needed. Then imagine that you are a kid in a group of peers, and that you are about to try a new physical activity where you might look awkward, and somebody might laugh at you. They get NERVOUS HANDS, clenching anything they hold with a death grip!

Without some forewarning, a group will have the gliders in shreds in minutes. I say things like, “It’s like having a pet butterfly”. I tell them to always be aware of what their hands are doing and relate how I have the same problem. I tell them about how careful they have to be before they actually handle the gliders and continue to remind them throughout the session.

Feeling how to fly is better than being told.

I could yap on and on with flying tips: keep the deflecting board more vertical like a wall, keep the glider high on the board; don’t let the glider get ahead; gain altitude and steer…nobody can keep so many things in mind at once! I have learned that teaching how to fly is best done tactile-kinesthetically.

My most effective teaching is walking next to people–whether it is little kids, teenagers or adults. I tell them that we will both hold onto the board but let me actually control it. I launch the glider, since that’s yet another thing to think about. After flying together for a bit I say, “It’s all yours” and let them take over. I observe how they crash it. Did they steer it into the wall? Did the glider just slowly keep losing altitude? Did they flatten the board instead of keeping it sloped? Whatever the problem is, I walk with them again. I do a little of whatever they did wrong, then correct it and again hand it off.

After a few such walks many people are flying well in minutes–not because they understand or remember all the tips, but because they are gaining an unspoken feel for flying. Of course, this means that you have to learn how to fly ahead of time. I urge you to do this anyway. Someone in the room should actually know how to fly walkalong gliders; it will save a lot of frustration.

Teaching people to fly walkalong gliders is easier than actually building the gliders. Teaching people to fly, but not build, might be better at some events.

I love to make things, and I love to set up teaching situations where people are making things. And I have bent over backwards (an idiom) making written instructions and video about how to make walkalong gliders. However, from experience I know that there are some situations where teaching a group of people to fly with already-made gliders works better than making gliders. If you don’t have much time, (perhaps 1 1/2 hours) think twice before getting yourself into a situation where you are frantically trying to finish. That will just lead to chaos. Another thing to think about is the age of the group. Many kids starting at age 10 or so have acquired the hand/eye coordination to fly gliders. But I would not make the gliders with a group unless they were at least teenagers (and even many teenagers have difficulty following directions). It’s a different dynamic when you are working with just a few people, but this article is about working with groups.

If you are not sure, consider this possibility: Perhaps you can set up one event where you just teach the group how to fly. Then, if that goes well, you can have another event where they make the gliders. You will have had a chance to get to know your group. Were they gentle with the delicate foam gliders when flying? If not, constructing is going to be even more difficult.

In this video from a language school in Japan, they started out with ready-to-fly gliders. About 1 1/2 minutes in they try to land the gliders on a table–a good activity for beginners.

Even if you do decide for the group to actually make the gliders, have your group fly some gliders first. Make them only after they have flown. Have some gliders ready to go.

I know that sounds backward. You would think that it makes more sense to make, then fly, right? I did it that way for years. Here’s why I switched.

Flying is easier than making. When you fly first, then building gliders makes more sense. Even if people have experience with origami, there are many parts of constructing the gliders that are counterintuitive. But if they fly the glider and see how the glider is made, then they are less likely to make a mistake when building. Instead of one giant step (building and flying), you break it down into two easier steps–flying, which is easier; then building, which is made easier by the first step of flying.

Practice flying before the event.

I know, we’re all busy, but I think it’s a good idea for people to know what they are doing before teaching others. Maybe that is obvious, but I often see people try to figure it out at the same time people are depending on them for direction. If you are making gliders with the group, make a couple of gliders before.

I can think of a possible exception to the “practice ahead” rule. If you are working with a group of sharp high school or college students–and you know that they can follow instructions–then they might be able to figure it out themselves with the video or written/ illustrated instructions. But I think middle school and younger students will need more of your guidance.

Consider the ratio of students to you, the teacher.

When I hear from someone who is very enthusiastic but does not have much teaching experience; and they tell me that they plan to get 30 kids making and flying gliders, I see disaster ahead. It is not even enough to have some other helpers in the room. In my opinion, they have to be helpers who have practiced ahead of time, just as you have.

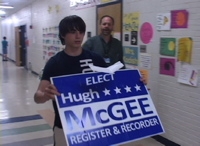

But once you know that, amazing things are possible! I got some wonderful feedback from Shannon Babb with Utah State University Extension and STEM coordination with Utah County 4-H. Through teamwork, Shannon reported that they got nearly a thousand people flying.

“Oh my goodness, the event went so well. The teens had so much fun learning how to make the gliders and caught on so quickly, that they wanted to teach some of the younger youth how to fly gliders at the aviation event that was open to all ages later that evening. I will admit I was a bit nervous about doing the activity with a young age group, but the high schoolers really stepped it up and worked one on one with the younger kids. By the end of the evening, everyone was thrilled to have interacted with the gliders whether they had the skill to figure out how to fly them or not.

“Now that we have an experienced teen volunteer base that are interested in teaching all ages how to fly, and older youth and adults know how to build the gliders, I have a feeling that they are going to worm their way into a lot of future activities.

“Honestly if the teens hadn’t taken charge there is no way that the walk-along glider activity would have worked without their leadership.”

Be aware of the psychology of your group. Some adolescents are terrified of being in situations where they might look stupid.

Most of the time I see nothing but unbridled enthusiasm when I am teaching people to fly. However, air-surfing gliders is a physical activity, and a very new physical activity at that. Like all new things, sometimes we look a bit awkward and silly until we get it. I find that at about 13 or 14 years of age, some kids become very extremely selfconcious when they are in groups, and this can be a very destructive group dynamic when trying to get them to do something new. When adolescents feel vulnerable to judgment or teasing, some shut down and stop trying. Obviously, you will want to create an emotionally safe atmosphere and nail teasing before it starts.

Some people will disagree with me about this next tip, but I also try to start with low expectations. I tell them that it took me days to learn air-surfing (true) and that I don’t expect them to be able to do it in just one day. So if they don’t get it, they retain some dignity. If they do get it, then they are quite happy (and sometimes you see the other side of insecurity: obnoxious bragging). So maybe you won’t use my methods; but do be mindful that with some age groups, psychology can be a force to be reckoned with.

Think about the space your group will need for flying. Be mindful of air turbulence (take note summer camps).

I do not live in a very windy region but, except at dawn and dusk or certain completely overcast days, it’s impossible to air-surf outside. The very slightest breeze that you can barely feel on your face is too much. That does not mean that you need a gymnasium. With the very low-density foam I call Time Warp, the gliders fly slowly and are maneuverable even in small rooms. And for larger groups, the wide halls, lobby, cafeteria and auditoriums in public buildings work well. But, always scout out the location first. Many science museums and even some schools have aggressive ventilation systems. Be sure that there are calm places with still air, or else flight will be impossible.

Encourage your group to spread out.

Kids are very social, and they often clump together even when there is enough space. But it can be a problem even if they are not actually colliding. People moving through the air create air turbulence. Try flying a glider walking behind someone walking a few feet ahead of you. It’s impossible because air swirls behind people in turbulent, circular vortices.

Links

This article is about flying walkalong gliders, and that opens up teaching moments about flight.

- Walkalong gliders stay in the air the same way that hang gliders can stay up for hours; by flying in rising air. Although this video is about hang gliders, much of it applies to walkalong gliders.

- I am starting to hear of people who are using walkalong flight as an analog for piloting, particularly cadets in CAP (Civil Air Patrol). It’s a great way to get a feel for takeoff, flight patterns, turbulence, approach and landing. This is an old but still good video about aerodynamics and piloting.

- Once people get a feel for flying, some will experiment with their own designs. One popular branch is bio-mimicry.

- Like all good science discovery stories, walkalong gliding history is full of people with unconventional ways of looking at the world, catastrophic and fortuitous accidents, serendipitous insights, cross-pollination, community and collaboration. You can see interviews with the historical innovators here. And a little farther down the page you can see links to You Tube videos of other people doing interesting things with walkalong gliders.

Thanks for taking the time to show others how to fly. Please let me know of your successes and challenges. I don’t have all the answers. If you have tips that worked for teaching with a group, share them.

Slater Harrison aka SciencetoyMaker