A classic folk /science toy gets easy to make

I don't care if my ancestors were playing with this folk toy a century ago. It is as magical today. And it will be just as fascinating to future generations even if we harness nuclear fusion for power and interplanetary travel becomes routine. That's what "classic" means: timeless, immortal.

The Propeller Stick

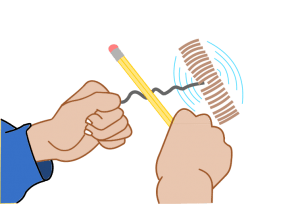

If you haven't crossed paths with a magic propeller stick (also known as a whimmy-doodle in Appalachia), you're in for a treat. You hold the stick in one hand and rub bumps on it with another. Mysteriously, the propeller spins fast... really fast. Some people can make it reverse direction at will.

There is some cool science going on here. In the "more about" page I will make the case that this propeller is closely related to such seemingly disparate subjects as hula-hoops and modern industrial fasteners. This project lends itself to endless experimentation. Change the propeller shape? Sure! Make multiple propeller heads like a mythological Hydra? Go ahead and try it. I have a lot of fun when I make this project with groups of kids, seeing the creative variations they come up with.

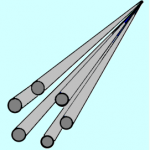

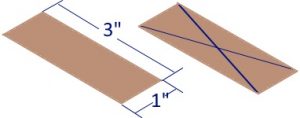

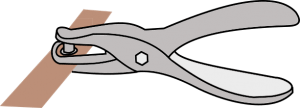

Traditionally, people have whittled notches into a wooden stick with a pocket knife to create the bumps-- not a very safe elementary project. I offer this easy-to-make version that uses a coat hanger or other wire with a couple of wavy bends instead of the whittled notches.

Feedback

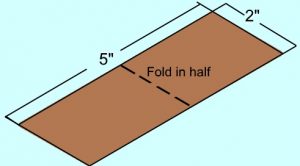

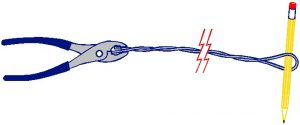

Bob William in the U.K. volunteers at a kid's club, bringing lots of hands-on science activities and projects. Bob came up with a clever bending jig to make the propeller stick available for 30 kids. Bob used 2.5mm copper cut to 25cm (10 inches). Copper could be expensive, but he had it leftover from an old job.

An 8 year old helper stripped off some of the insulation and the kids--at least 7 years old--used the bending jig themselves. If someone was unsure or having difficulties, 10 year old helpers assisted them.

Bob has made air and water rockets as well as rubber band-powered planes with various groups. I had to laugh when he wrote, "I have another meeting on Wednesday for mixed ages from toddlers up so I'll present the popular "moose call" activity. Thanks for that, although some parents may express other sentiments when the kids get home."

Michael Deal, a retired Physics teacher and model airplane enthusiast, also in the U.K., has been coaching me about amazing projects like camphor boats, rattlebacks (he made one out of a spoon) and magnet toys--often things that spin mysteriously. I hope share them on this website when when I get caught up. And this is the most creative propeller stick that I've ever seen! He makes them as Christmas presents, calling them "Sopwith Crocodiles". The Snoopy figures are so intricate that I thought they must be bought, but a close look at the farthest reveals that it's a prototype. When I asked about it, Michael said one trick is to add the oven-hardening mouldable plastic in stages--heating multiple times in the oven is not a problem. He used internal wire, especially for Woodstock (which represents the "Spirit of Ecstasy" mascot on Rolls Royce cars. Snoopy is giving the thumbs up to the ground crew (you) to start the engine.

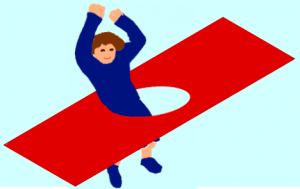

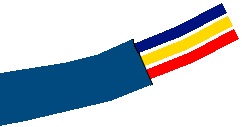

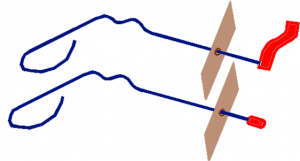

If you could use time-lapse photography to show the motion of the wire at the end of the propeller stick, I believe you would see a circular vibration such as the illustration on the right. Notice that the motion is similar to what you would do with your hips to make a hula-hoop spin.

If you could use time-lapse photography to show the motion of the wire at the end of the propeller stick, I believe you would see a circular vibration such as the illustration on the right. Notice that the motion is similar to what you would do with your hips to make a hula-hoop spin.

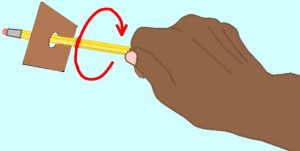

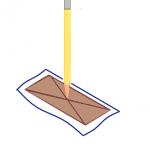

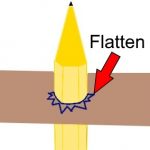

If you are right-handed, hold a pen or pencil in that hand. Hold the pencil--not horizontally and not vertically--but at about a 45 degree angle. Grip the propeller in the other hand. Push the pen to the bumps firmly and rub. Once you "get it" it will be easy to get the propeller to spin furiously, but allow a few minutes this first time. Experiment. Rub fast, rub slow, hard, soft, vary the angle of your pencil.

If you are right-handed, hold a pen or pencil in that hand. Hold the pencil--not horizontally and not vertically--but at about a 45 degree angle. Grip the propeller in the other hand. Push the pen to the bumps firmly and rub. Once you "get it" it will be easy to get the propeller to spin furiously, but allow a few minutes this first time. Experiment. Rub fast, rub slow, hard, soft, vary the angle of your pencil.