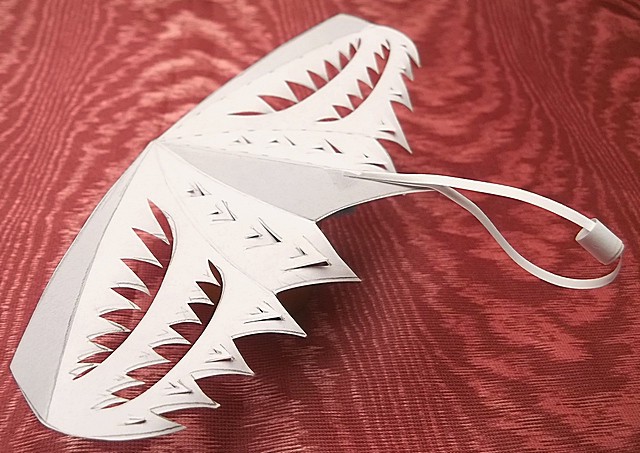

As I track walkalong glider development throughout the world, I meet really interesting people, such as Ken Evans in the UK. He sent me a picture of the most elegant Jagwing that I can imagine; almost a work of art (Mike Thompson’s Jagwing design is usually basic, simple and easy to build/fly). I was a bit guarded. Did it fly? Ken assured me that it did and started sharing his thought process:

Click to Enlarge images

"The jagwing type in the first image I sent you is just Mike's basic model with some corners knocked off. That's partly an attempt to align each jag head-on to the airflow when the wing is given dihedral and during turns, but I also just prefer curves over straight lines. Folds and corrugations hold their shape better when they are curved.

'Filigree' designs (with holes in the wings) should allow air to escape from the high-pressure zone beneath the wing into the low-pressure region above. This kind of 'bleed' is usually considered undesirable, but I think lift could be extracted from the airflow while it is moving upwards relative to the wing. One method might be to put Mike's leading-edge 'comb' at the back of a vent or slot. 'Stacking' or 'nesting' the points behind each other may be another way to achieve it.

Sliding noseweights allow very precise trim control."

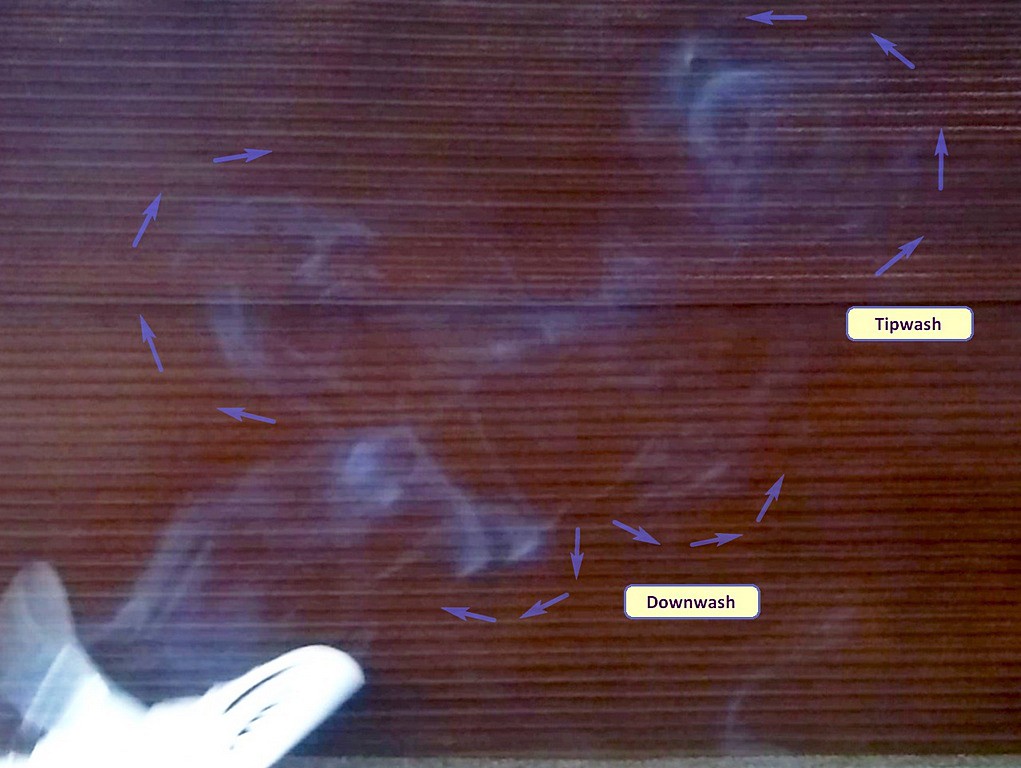

Next, Ken proposed to use smoke to visualize airflow as a glider passed. I was skeptical. Lots of walkalong glider enthusiasts had the same idea, but nobody had pulled it off. Indeed, Ken’s first attempts appeared to me more like Rorschach patterns than anything visually informative, to non-experts.

But Ken was only just starting. When I mentioned the stunning images I'd seen of planes down-washing air into clouds below, he shifted from incense smoke to ultrasonic fog in a container.

The clips he sent to me neatly demonstrate how Newton's Third Law of Motion gives the lift needed for air machines to fly.

“I work as a Theatrical Technician, although my University subject was Architectural Technology. I am a keen (but mediocre) Archer, and my interest in aerodynamics followed on from studying how the arrows work.

I find Flight fascinating because there is a lot of 'design headroom'; that means a big gap between what we have achieved and what we know to be possible. The aircraft we use apply massive quantities of power in order to solve the problem of getting airborne, while birds, bats and insects use a very wide range of flight techniques to perform astonishing aerobatics or to travel vast distances, often on very little fuel.

That's the sort of thing that makes me curious, and Walkalong Gliding seems like an ideal playground for trying out new ideas (and re-examining older ones), without breaking the bank or getting injured as the pioneers of full-scale flight often did.”

Also, in the course of corresponding, Ken expanded my world with tidbits such as follows, about a flight pioneer who predated the Wright Brothers. Horatio Phillips did important work with curved airfoils and he is known for (to modern eyes) silly planes with lots of stacked wings that sometimes fell down. But Ken shared a deeper look:

“My belief is that there's a great deal to be learned from 'blind alley' developments that have been eclipsed by more 'correct' solutions which caught on and became familiar to us.

In aviation, a prominent example is the English pioneer Horatio Phillips, who did a vast amount of wind-tunnel testing on wing shapes in the 1880s. For some reason, he decided that for best effect these lifting profiles should be stacked up in huge numbers (say, 200 wings, all 18 feet span and around 3 inches chord). He wasn't completely wrong, either. His steam-powered machines generated enough lift to take off in a captive-testing rig.

Clips of similar 'venetian blind' machines are now mainly used for entertainment, because in trials for free flight the inadequately supported wing array often crumpled spectacularly. Development in any field is usually portrayed as competitive, so unsuccessful projects are routinely written off as pointless or even insane.

My guess is that the multiple wing array probably has unappreciated merit. Distracted by L-ing our A off, we haven't yet rediscovered the driving principle that motivated Horatio to stack them so enthusiastically.

Judging by your website, you still seem very excited by the diversity of thought to be found in the field of miniature aviation right now.”